|

| | A technician slides a SelectaVision video-disc player into its outer cover at RCA’s new plant in Indianapolis |

Two disc machines that let you program your own shows will be introduced in '77

Sometime this year, TV viewers in selected areas of the country should be able to schedule their own shows in an entirely new way. They’ll select movies, musical performances, or other material on video disc, slip the discs into players wired to their receiver’s antenna terminals, and push a button to watch the show.

A long list of glittering new video players has been promised, postponed, or introduced in recent years, only to fade from sight. But there are definite signs that at least two major worldwide organizations with the financial muscle and marketing know-how to succeed will begin selling their video-disc players regionally in 1977.

One of them, RCA, is already field-testing a few hundred of its capacitance-sensing SelectaVision disc players. N.V. Philips, the Dutch firm that brought us the standard audio cassette, and MCA Inc., an American entertainment-oriented firm, also plan to offer an optical video-disc system this year.

The latest price estimates: about $500 for the player, and $10 to $18 for a disc or set of discs.

There’s even a possibility that a Japanese licensee of a British and German disc venture, the grooved-disc TED system [PS, Nov. ‘74], could be marketing disc players, too. Players for 10-minute TED discs have been available in Germany since 1975, although only for European TV-signal standards. Sales have been poor. A TED changer that handles 12 discs was recently shown. Spinning on the sidelines are other disc systems still under development [see box: “In the labs: machines that record and play discs”].

Both the RCA and Philips/MCA players will appear in stores just when new home video-cassette recorders [PS, Dec. ‘75], video games [PS, Nov. ‘76], and pay-cable programming are teaching viewers that their TV receivers can easily display something other than fixed-time broadcast fare.

What’s different about the new disc hardware and programming? After operating both the RCA and Philips/MCA players, trying some amazing manipulations of TV images, and listening to stereo hi-fi TV sound I found that the new machines offer spectacular gains in performance compared with other home program sources.

Stamping out tons of discs at low cost is the biggest advantage of the new medium. Both Philips/MCA and RCA expect to offer a broad selection of discs when their players appear. MCA, which will manufacture most U.S. discs for the Magnavox-built player, plans 1000 albums initially.

MCA discs will include new and old films, ballet, opera, theater, sports, how-to and children’s programs, and documentaries. MCA can also make a thin flexible disc that might be inserted in periodicals. Discs may also be distributed as entire magazines, catalogs, or talking encyclopedias.

Also, a variety of independent companies will add other special-interest discs to catalogs. One firm, Visiondisc Corp. of New York, for example, planned to tape last year’s Christmas services and works of art at a large cathedral for transfer to discs.

Here’s how the two leading players and disc formats differ:

RCA’s SelectaVision

This machine is designed to play a rigid, grooved disc 12 inches in diameter and programmed on both sides with 30 minutes of material. The function of the spiral groove is to guide a stylus, much as in an audio-disc system. This machine is designed to play a rigid, grooved disc 12 inches in diameter and programmed on both sides with 30 minutes of material. The function of the spiral groove is to guide a stylus, much as in an audio-disc system.

But that’s the end of any similarity to familiar 33-1/3- or 45-rpm discs. The SelectaVision player, which won’t operate unless the lid is closed, spins discs at 450 rpm. TV signals are encoded as minute rectangular depressions at the bottom of each groove. The slots vary in spacing and width, with some as narrow as 0.25 microns (millionths of a meter), RCA devised a method of producing the slots on a disc master, using a sharply focused electron beam, since required widths are too narrow to be generated optically with light. The discs have a vinyl base topped with thin layers of metal, an insulating plastic (dielectric), and an oil lubricant that reduces stylus wear.

Together, the disc and metal-tipped stylus form an electrical circuit. As the slots spin past the stylus, tiny abrupt changes in circuit capacitance occur. These changes detune an oscillator circuit to produce the TV signal.

To compensate for small changes in rotational speed, a tiny transducer, which functions somewhat like a loudspeaker coil and cone, stretches the stylus arm back and forth parallel to the groove. Errors in speed are detected by monitoring the recorded color-burst signal.

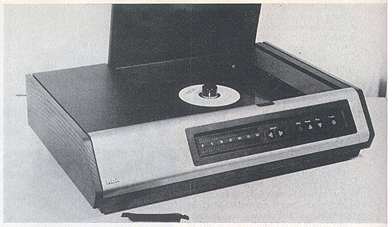

A close look at a SelectaVision player confirms RCA’s disc-system design philosophy. Components are housed in a simple, inexpensive cabinet with a minimum number of controls. Internal circuit boards and components, prominently displayed on a pegboard in RCA’s New York demonstration room, remind you of a Heathkit spread out for assembly. RCA deliberately designed a player that could be easily mass-produced with relatively standard parts.

Care is necessary when loading discs in the machine, since fingerprints or smudges can create interference. Playing discs repeatedly through can remove contaminants from the grooves, but since the $15 stylus must be replaced after 200 to 300 hours of use, it’s wiser to take good care of records. Each disc can be played about 500 times.

Pictures I’ve seen at several demonstrations were excellent. You can rapidly move the tangential stylus arm forward or backward to selected disc areas by pushing buttons; a lighted index on the panel becomes larger or smaller. A pause button breaks stylus contact. The player has two audio channels for stereo or bilingual programming, and audio output jacks for optional connection to a hi-fi amplifier.

Philips/MCA Player

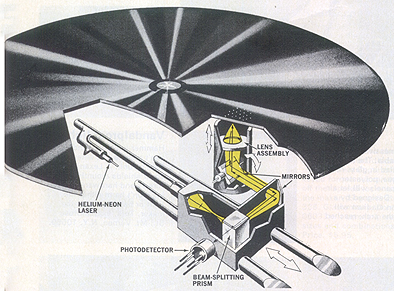

This concept differs radically from SelectaVision. Only the center spindle touches Philips/MCA discs as they spin at 1800 rpm. An air bearing that develops at that speed aids stabilization. A low-power laser beam, focused to a one-micron spot, strikes the bottom surface of the aluminum disc [see diagram]. This highly reflective layer has a clear-plastic protective coating. The beam falls on a spiral track that consists of oblong bumps of varying lengths, with flat areas between them. The encoded picture information varies the distance between bumps. Part of the laser light is reflected from the flat area between bumps back through the optics to a light-sensitive diode that detects the TV signal. Only one side of a disc is programmed, with 30 minutes of material. This concept differs radically from SelectaVision. Only the center spindle touches Philips/MCA discs as they spin at 1800 rpm. An air bearing that develops at that speed aids stabilization. A low-power laser beam, focused to a one-micron spot, strikes the bottom surface of the aluminum disc [see diagram]. This highly reflective layer has a clear-plastic protective coating. The beam falls on a spiral track that consists of oblong bumps of varying lengths, with flat areas between them. The encoded picture information varies the distance between bumps. Part of the laser light is reflected from the flat area between bumps back through the optics to a light-sensitive diode that detects the TV signal. Only one side of a disc is programmed, with 30 minutes of material.

By shifting the beam spot slightly on the spinning disc, three sophisticated servo circuits maintain focus, tracking, and proper speed. The servos sense deviations by monitoring auxiliary beams reflected from the disc. Corrections are made with electronic signals that can shift the focusing lens up or down; or, to compensate for radial (sideway) and speed errors, two mirrors positioned at right angles to each other can be pivoted to shift the beam spot.

Jolting a player

Despite the extraordinarily small tolerances involved, the servos do their jobs remarkably well. Even a sharp rap on the Philips/MCA layer case – enough to jolt an audio-cartridge stylus from its groove – does nothing, or produces only a brief flicker on the picture.

Philips/MCA discs can be handled easily without concern for smudges or dust. The thick protective coating keeps blemishes out of focus, which prevents picture interference. Discs should last indefinitely, since there’s no wear from playback. The helium-neon laser “stylus” lasts a minimum of 10,000 hours before replacement may become necessary.

There’s a distinct look and feel of compact precision to the Philips/MCA player. The front panel is packed with controls that capitalize on the contactless readout and the fact that each revolution of the disc produces one TV picture.

One button lets you indefinitely freeze any one of 54,000 picture frames for in-depth viewing on the screen. Other controls enable you to advance the picture sequences manually, frame by frame, forward or backward. A variable-speed control does the same thing automatically.

Counting Frames

In the fast-scan mode, pictures become a blur; however, every few seconds one is frozen for an instant to help pinpoint a location. All Philips/MCA discs will be encoded with signals that serve to identify each frame. Tap another button and the frame numbers appear in a corner of the TV screen. The player has stereo hi-fi output jacks and a video-output jack (a non-RF signal).

Both RCA and Philips/MCA have invested perhaps several hundred million dollars without knowing whether consumers will buy the players and discs to program their own shows. If the spectacular climb in sales of video-cassette recorders, TV-game, and pay-cable systems are any indication, the video-disc manufacturers have made a shrewd investment.

A stylus that detects picture signals in grooves A stylus that detects picture signals in grooves

RCA SelectaVision player (far left) spins rigid 0.07-inch-thick discs at 450 rpm. Discs carry 30 minutes of material on each side. TV signals are detected by a metal-tipped sapphire stylus tracking at about 50 milligrams in a spiral groove. Picture information is recorded on discs as microscopic slots of different width and separation. The metallic stylus senses a change of electrical capacitance as the slots spin beneath it. This capacitance variation changes an electronic signal that is unscrambled into TV pictures. Metallic and dielectric coatings necessary for playback give SelectaVision discs a shiny appearance. There are 5555 grooves per inch, and each circular groove stores four 1/30-second TV frames. The player has fast-forward and reverse buttons for cueing.

Laser-beam system decodes a spiral track of bumps

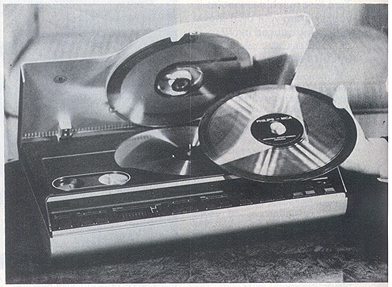

Philips/MCA optical video-disc player (far left), manufactured by Magnavox, rotates discs at 1800 rpm. Players can handle either rigid 0.04-inch-thick discs, or, with an adapter, 0.007-inch flexible versions. Nothing contacts the disc for picture readout: A laser beam is focused through a mirror/lens system onto a spiral track of bumps on the bottom of the disc. Spacing between the bumps varies according to TV picture information. The bumps scatter the beam, but the flat, shiny aluminum area between them reflects light back through a two-way prism or mirror to a photo-diode detector. The detector circuits convert the code-like flashes from the disc into a TV signal. Tracks are less than two microns (millionths of a meter) apart. The player can endlessly freeze a TV frame, show fast or slow-motion pictures, and display on the screen the number of up to 54,000 separate coded frames. Discs hold 30 minutes of programming on one side only. Philips/MCA optical video-disc player (far left), manufactured by Magnavox, rotates discs at 1800 rpm. Players can handle either rigid 0.04-inch-thick discs, or, with an adapter, 0.007-inch flexible versions. Nothing contacts the disc for picture readout: A laser beam is focused through a mirror/lens system onto a spiral track of bumps on the bottom of the disc. Spacing between the bumps varies according to TV picture information. The bumps scatter the beam, but the flat, shiny aluminum area between them reflects light back through a two-way prism or mirror to a photo-diode detector. The detector circuits convert the code-like flashes from the disc into a TV signal. Tracks are less than two microns (millionths of a meter) apart. The player can endlessly freeze a TV frame, show fast or slow-motion pictures, and display on the screen the number of up to 54,000 separate coded frames. Discs hold 30 minutes of programming on one side only.

In the Labs: machines that record and play discs

As the big contenders (RCA, N.V. Philips, and MCA Inc.) gear up production lines to produce capacitance and optical video-disc systems (diagrams above), other companies and institutions are busy refining other ingenious disc systems in laboratories. Although developers of new players frequently say they plan to market them, the huge expense of manufacturing and distributing a major new product today may prevent you from ever seeing most new systems in stores. Some of these disc systems are intriguing because they can record TV programs as well as play prerecorded discs:

A magnetic disc recorder (MDR) has been under development for several years by Erich Rabe, a German record manufacturer [PS, Nov. ‘74]. The latest version, demonstrated last year in Europe, presented poor color pictures. Meanwhile, a U.S. licensee, TV Disc Corp. in Waltham, Mass., is developing its version of MDR. The Rabe recorder/player, similar in appearance to an audio turntable, has a tone-arm-mounted recording head that rides in the grooves of the magnetic disc. The head can record 24 tracks in the groove walls, and might provide two-hour discs. Early 12-inch discs of this type played at a slow 158 rpm.

Another disc-recorder system, developed by University of Toronto professor John Locke and a graduate student, encodes TV signals onto a specially formulated plastic with a low-power laser beam. Locke told the trade weekly, Television Digest, that he expects a home video-disc recorder would use a dual-power laser. The higher-power beam – perhaps only two milliwatts, or twice that of the Philips/MCA readout laser – would record, and the low-power beam would play back. Locke says he is in touch with potential manufacturers.

In Japan, Hitachi Ltd. has developed a holographic video disc (playback only) that eliminates the complex focusing and tracking devices used in other optical systems. (Holograms are photographic images made with laser light.) The disc system, described in the June, 1976 Applied Optics, employs a continuous train of one-millimeter-square holograms on the disc’s surface. Each hologram is actually three separate images (for brightness, color, and sound) offset 120-degrees from each other. The disc rotates at only six rpm.

|